July 14, 2017

I am a chile head.

I also like coaxing a tremendous amount of flavor out of a small number of ingredients (though I don’t shy away from recipes with long ingredient lists either!).

I am a big fan of dishes that can be made in advance and warmed up for serving. Carne Adovada actually tastes better if it is refrigerated for a day or two.

For all of these reasons, Carne Adovada is an ideal dish for me. It is, bar none, my favorite New Mexican dish.

However, it isn’t necessary to use hot or extra-hot red chile. If you’re not a fan of spicy foods, use mild or medium-hot chile. What is critical is that you use actual New Mexico dried red chile.

Although I rode in a car along route 66 in the 1960s to visit an uncle in Los Angeles, I never spent any appreciable time in New Mexico until August 1991. Just days into that week-long visit to Santa Fe, I had Carne Adovada at Maria’s Restaurant.

I was hooked!

I was also enchanted by Santa Fe, as was my husband. By late 1992 we put in an offer on our first house in Santa Fe. The offer was accepted and we closed in January 1993. Thus began our love affair with Santa Fe.

We moved to Santa Fe full time in 2012 but we spent considerable time in Santa Fe every year until then (about ten times per year including all major holidays).

I was never happy with any Carne Adovada recipe that I tried, and I tried plenty, until I stumbled on a recipe from Al Lucero, the former owner of Maria’s Restaurant, in the program book for Santa Fe Wine and Chile Fiesta a number of years ago.

In times past, when a hog was butchered in the fall, some of the meat was preserved in red chile. This chile-infused meat was later braised to become Carne Adovada. I don’t know of anyone who cures pork this way any longer but many recipes for Carne Adovada call for marinating the pork overnight in the red chile. This would seem to be closer to the traditional method, though simply marinating the meat would not produce the additional flavor that would come from actually curing the pork in the chile. Some recipes, though a minority in my experience, call for the addition of vinegar to the marinade to try to achieve more of a “cured” or “fermented” flavor.

Al Lucero’s approach is different but definitely creates an extra layer of flavor. The pork cubes are roasted first then braised in red chile. Refrigerating the completed Carne Adovada for a day or two before serving improves the flavor even more.

What I especially like about Al’s method is that it does not introduce any non-traditional ingredients to the Carne Adovada. Until I can taste Carne Adovada made from pork that is actually cured in red chile, I’m sticking with my tweaked version of Al’s method.

Click HERE to join our mailing list and you’ll never miss a recipe again!

| Prep Time | 30 minutes |

| Cook Time | 5 hours |

| Servings |

people

|

- 5 pounds pork butt cut in 1 inch cubes

- 4 teaspoons garlic powder

- 5 teaspoons salt

- 8 ounces dried New Mexico chile pods weigh the chile pods after stems and seeds are removed

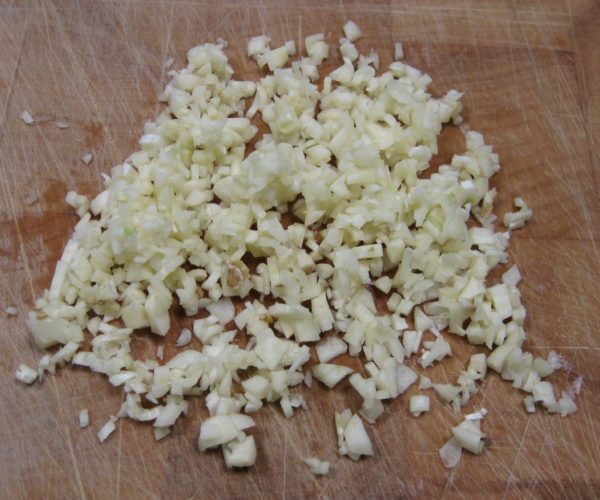

- 10 cloves garlic minced

- 5 1/2 teaspoons salt

- 7 1/2 cups water

Ingredients

Pork

Red Chile Sauce

|

|

- Cut the pork into one inch cubes.

- Toss the pork with the garlic powder, and salt.

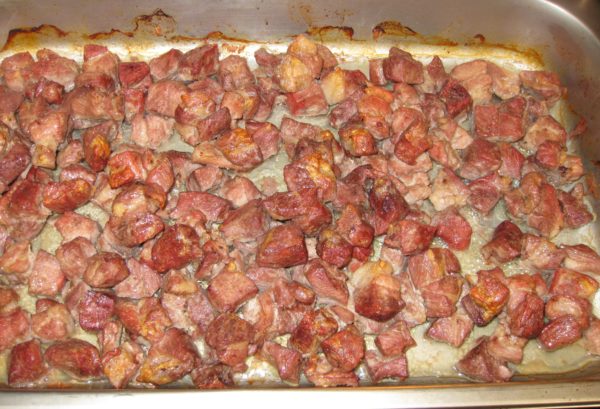

- Put the meat in a wide shallow baking/roasting pan that has a lid and roast at 450°F, uncovered, until well browned, turning every 20 minutes or so, approximately 90 minutes.

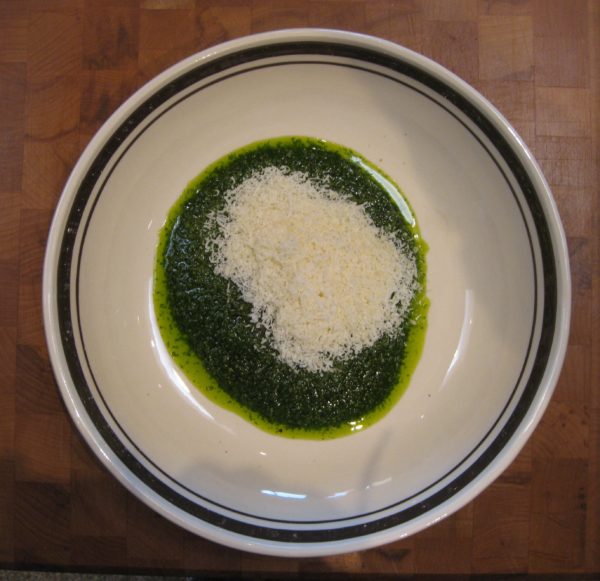

- While the pork is roasting, make the red chile sauce using the proportions of ingredients called for above and following the directions in the Red Chile blog post. See the "Notes" section below for the link. There is some rendered fat in the pan. Do not discard the fat, it carries lots of flavor and improves the mouth feel of the sauce.

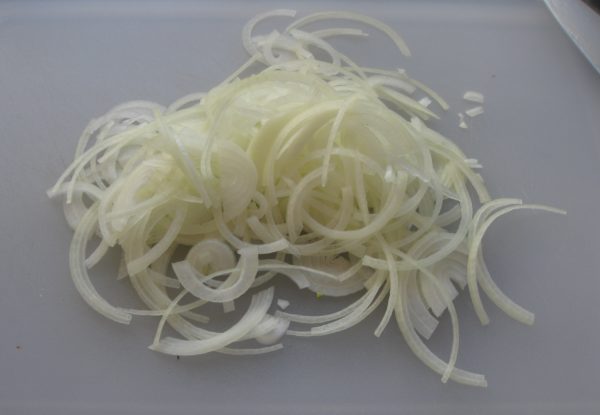

- Beginning to brown.

- Tossed after the top has browned.

- Almost brown enough.

- Browned and ready for the chile. Note that the liquid has all evaporated and created a brown fond in the pan. This gives extra flavor.

- When pork is browned, add all the red chile sauce without draining any of the juices out of the pan.

- Cook, covered, at 250°F for approximately 3-4 hours or until meat is very tender, stirring occasionally.

- Remove the meat from the oven. Allow it to cool to room temperature.

- Cover tightly and refrigerate overnight.

- Reheat the carne adovada, covered, at 250°F for approximately 2 hours. If the sauce is not thick enough, reheat uncovered at a somewhat higher temperature until the sauce is thickened.

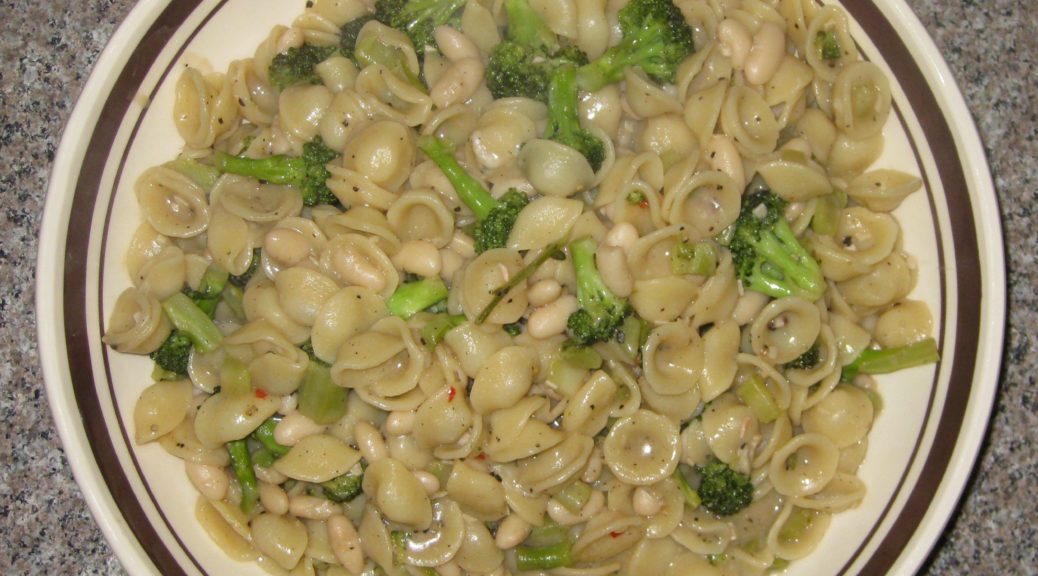

- This plate contains carne adovada, red rice, frijoles (beans), and calabacitas) (zucchini, corn, and roasted green chile).

Here's where you can find the directions for making Red Chile Sauce.

Copyright © 2017 by VillaSentieri.com. All rights reserved.