March 25, 2020

I’ve been at home now for more than two weeks with just a weekly shopping trip to take me “off the mountain” as we say in our house.

This has given me ample time to catch up on some projects and start others. It certainly gives me a lot more leeway to plan out a lot of cooking adventures.

Three days ago, I made 19 pounds of ‘ndjua. It was a great project for a Sunday. Well, these days, almost every day is like Sunday.

Making the ‘nduja, which is roughly 25% red pepper, wiped me out of the supply of peperoncino piccante in polvere (ground hot red pepper) that I brought back from Calabria in September. In fact, I had to supplement with red pepper from India that I bought at an international food store in Las Vegas, NV a couple of months ago for just such an eventuality.

Join our mailing list and you’ll never miss a recipe again!

I’ve used up half of my supply of nero di seppia (cuttlefish ink… what, in America, we call squid ink except that it’s not from squid…it’s from cuttlefish), also brought back from Calabria.

The same is true for my lievito madre, powdered mother yeast. It’s a combination of commercial yeast and “natural” yeast. It’s sort of like a sourdough starter except that it’s not sour and you don’t keep the culture going. You just use the powdered stuff as needed.

These are all common supermarket or open-air market items in Italy.

We have plans to spend a month in a villa in Calabria this fall. I have been honing my shopping list for months but I’m now concerned that the trip might not happen as planned. It’s still a bit too early to know for sure but I’m getting myself mentally prepared for cancellation.

Meanwhile, I do what I love. I cook. Even if it means that I might use up precious supplies with the prospect that there may be no reasonable means of restocking in the near future.

Follow us on your social media platform of choice

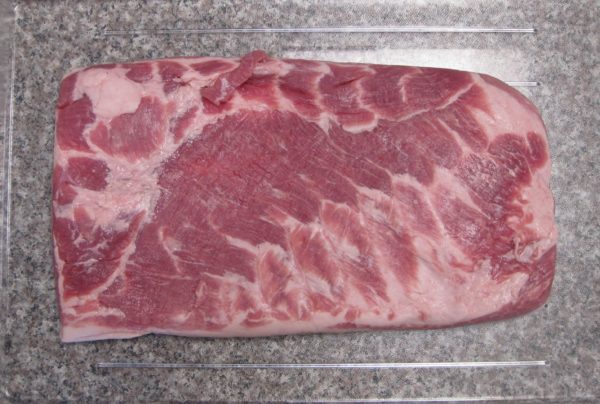

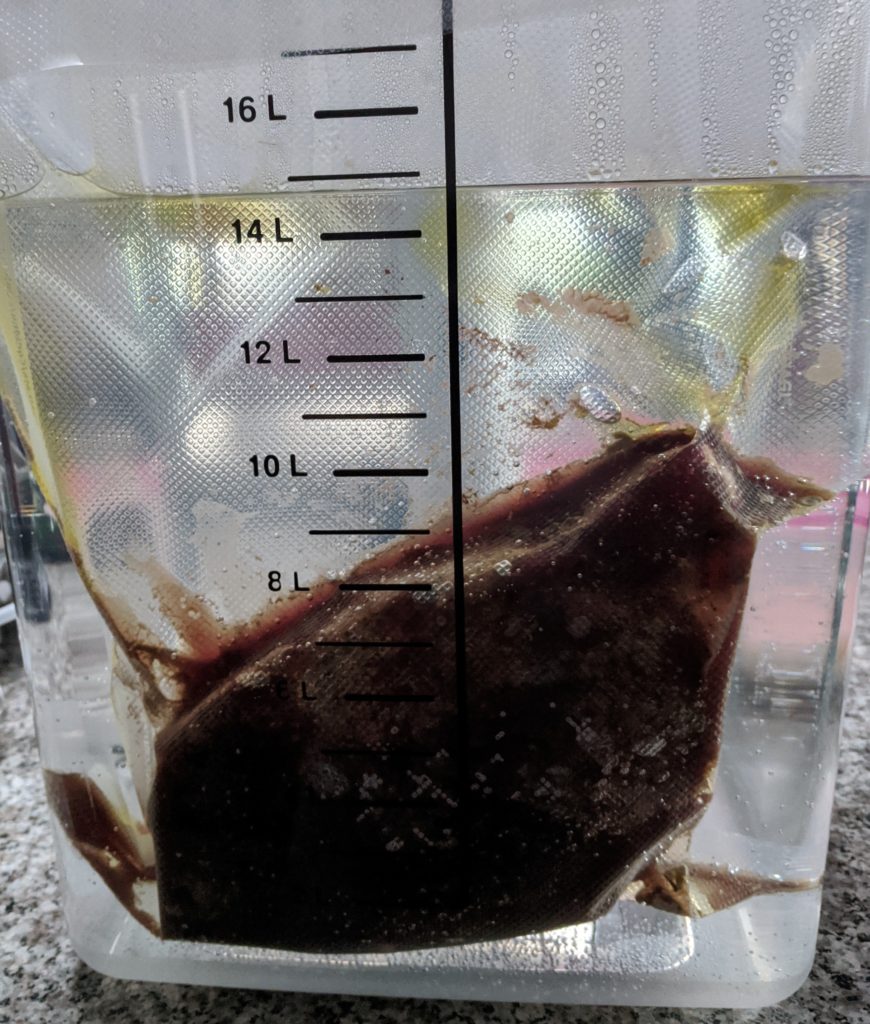

Two days ago, I made stuffed and rolled flank steak. One day last week I made a batch of black pasta (with, ahem, cuttlefish ink) that I tossed with fresh scallops and mushrooms. I made a killer sous vide rib eye roast on Sunday. It bobbed along, all seasoned up, in a vacuum sealed bag with my sous vide doing all the hard work while I made ‘nduja.

The ‘nduja was done, and hung, in time for me to pour a bourbon, take the roast out of the bag and sear it, and cook some veggies.

I’m comforted to know that in about two months there’ll be lots of ‘ndjua to enjoy.

If you’re stuck at home, why not consider making something new—like ricotta. All you need is milk, vinegar and salt (and, if you wish, a little cream). Once you’ve made ricotta, you can drizzle it with honey and serve it for dessert or turn it into Sancarlin and serve it with some garlicky crostini.

| Prep Time | 15 minutes |

| Cook Time | 20 minutes |

| Passive Time | 30 minutes |

| Servings |

pounds

|

- 9 cups whole milk

- 1 cup heavy whipping cream

- 1 teaspoon fine salt

- 3 tablespoons distilled white vinegar

Ingredients

|

|

- Warm the milk, cream, and salt in a heavy bottomed pan over medium heat.

- Stir occasionally until it reaches 170°F. Stir more frequently after that, and almost constantly once it reaches 185°F until the targt temperature is reached, 192°F or higher as described in the headnote.

- When it reaches the target temperature, add the vinegar and stir well. Turn off the heat and move the pot off the heating element. Even if you’re using a gas stove the grate will remain hot and can increase the temperature of the milk too much.

- Allow the milk to sit undisturbed. Curds should form a raft floating on top in 10 minutes. If curds do not form, add 1 tablespoon more vinegar, stir well, and wait 5-10 minutes more.

- Cut the curds into one-inch cubes with a knife.

- Lift the curds into cheese molds set on a grate to drain.

- Alternatively put the curds into a strainer lined with a double thickness of cheesecloth.

- Drain until the ricotta is as dry as desired based on how you plan to use it. The ricotta will be slightly stiffer once it is chilled so do not drain it too much.

- Once drained, the ricotta can be stored with the bottom sitting in a little of the whey to keep it moist. It will not reabsorb liquid once it has drained out.

Copyright © 2020 by Villa Sentieri, LLC. All rights reserved.