December 19, 2019

I try to cook seasonally.

That means no stone fruit or corn on the cob in the winter. For the most part that means no tomatoes either, though I do make an exception for cherry and grape tomatoes which seem to taste about the same year-round and provide a burst of color and sweetness—if not a robust tomato taste—in the dead of winter.

Certain things defy the season. Take zucchini. Yes, they’re the quintessential summer crop (sometimes growing to the size of baseball bats in the hands of inattentive growers) but they show up all year-round, much like bananas do.

I know that means they get shipped from “somewhere else” when they’re not in season locally but, for the most part, they taste good all year (unlike, say, peaches which don’t usually taste good if not grown locally and in season).

There’s also a limit to the number of cold-season vegetables that one can eat through the winter.

Join our mailing list and you’ll never miss a recipe again!

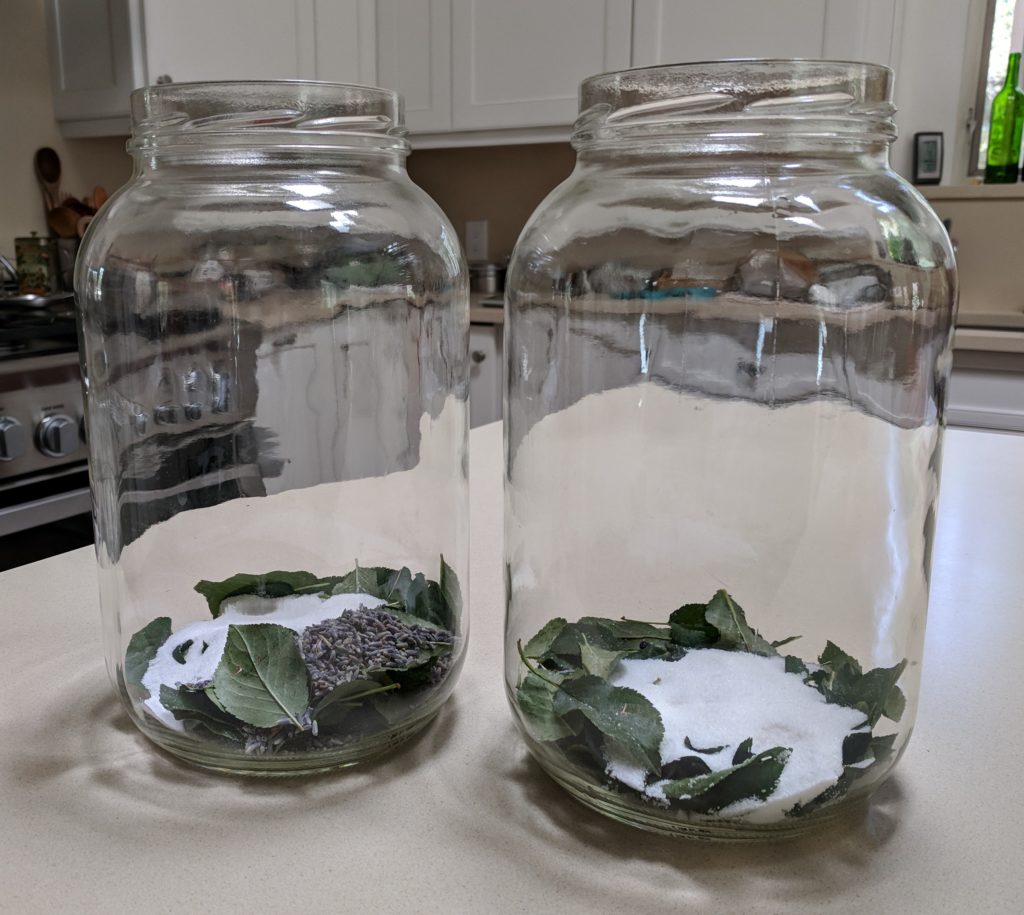

Part of the problem is solved by canning, preserving, and freezing and, if not your own or a friend’s, commercially available canned, preserved, and frozen produce. Let’s face it, eating seasonally traditionally included consuming all those products that were “put up” when they were at the height of season.

Though some of us conserve produce, few of us do enough to meet our needs throughout the lean winter months. I have no objection to using good quality commercially “conserved” foods. What I don’t use are convenience or premade foods.

Though I enjoy and prefer to make my own tomato puree (passata), we don’t produce enough of our own tomatoes to make a year’s supply (and I haven’t been overly impressed with what’s available in the market in sufficient and affordable quantity to make up the difference).

I do what I can, however, for example making passata when our tomatoes are at their best; candying citrus peels from the trees in our neighborhood in Palm Springs in the winter; making cherry leaf aperitif in the fall; and, in those rare years when Santa Fe has an abundance of peaches and apricots, making jam.

I “conserve” other produce as well like making hot chile oil (“olio santo”) when we have enough peperoncini, making limoncello and arancello from oranges and lemons in Palm Springs, and putting fresh (like cherries) and dried (like prunes) fruits in various types of spirits.

Follow us on your social media platform of choice

My prohibition on using “prepared foods,” though is pretty definite. I’ll use good quality canned, peeled tomatoes from Italy but (unless my back is up against the wall as sometimes happens when I have limited shopping venues like when we’re on Fire Island) I don’t use canned commercial diced or crushed tomatoes or tomato puree. My view, and, granted, it might be wrong, is that the best quality tomatoes go into the cans of “whole, peeled” tomatoes, not into the ones that are ground, diced, or pureed.

In a matter of minutes, a can of whole peeled tomatoes can be turned into any of the other products. It also means that, other than tomato paste, I only need to stock up on one tomato product. OK, OK, so I have two types of peeled, whole tomatoes. Both are from Italy but one is San Marzano and the other is a plum tomato that’s not San Marzano. I use the less expensive non-San-Marzano-but-still-Italian tomatoes when the dish I am making would be indistinguishable with either type.

In December, zucchini are a welcome addition to mealtime, a situation that is difficult to imagine during the fall harvest season when zucchini seem to be coming from all directions.

| Prep Time | 15 minutes |

| Cook Time | 30 minutes |

| Servings |

persons

|

- 4 medium zucchini

- 1/4 cup extra virgin olive oil

- 4 cloves garlic coarsely chopped

- 1 tablespoon chopped fresh niepita or to taste

- 3/4 cup pommarola or other simple tomato sauce

- 1 1/2 cups water

- salt

- Freshly ground black pepper

Ingredients

|

|

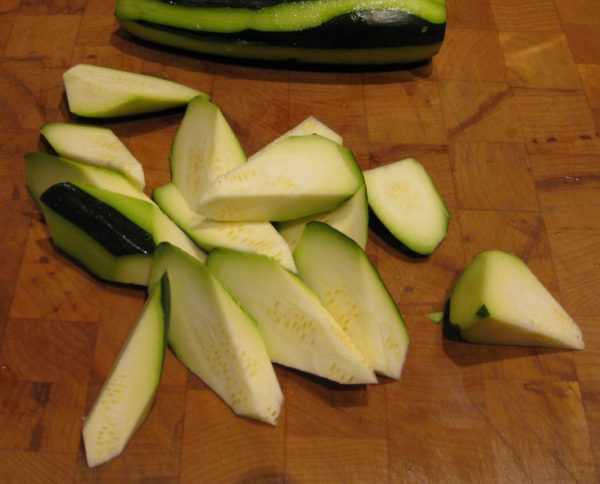

- Partially peel the zucchini, leaving alternating stripes of peel and no peel.

- Cut the zucchini into largish pieces. You can do this by quartering them lengthwise and then cutting crosswise or by doing a rotating angular cut. You should have approximately 2 pounds of cut-up zucchini.

- Sauté the garlic in olive oil until it begins to color.

- Add zucchini. Season with salt, and pepper. Increase the heat to high and sauté until the garlic golden brown and the zucchini has turned from white to creamy in color, approximately 5 minutes.

- Add the tomato sauce, water, niepita, and salt and pepper to taste.

- Cook at a moderate boil, uncovered, until the sauce is thick and the zucchini is tender but not mushy. Adjust salt and pepper while cooking.

You can find my recipe for Basic Tomato Sauce here.

Copyright © 2019 by Villa Sentieri, LLC. All rights reserved.